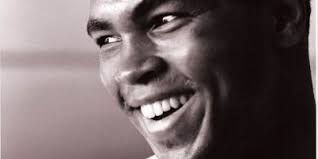

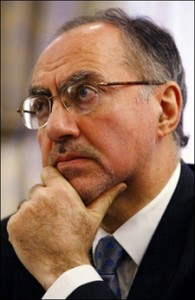

Ali Allawi

Few people combine real life experience with spiritual insight as much as Ali Allawi. He has a deep appreciation for the spiritual education once provided by the Sufi orders and the need for reviving an effective language of spirituality. We were delighted to learn that he is also closely associated with our dear friend, Shaykh Fadhlalla Haeri, and thus deeply acquainted with the path of spiritual experience. He has also held positions of responsibility as Minister of Trade and Minister of Defense in the cabinet appointed by the Interim Iraq Governing Council from September 2003 until 2004, and subsequently Minister of Finance in the Iraqi Transitional Government between 2005 and 2006.

Few people combine real life experience with spiritual insight as much as Ali Allawi. He has a deep appreciation for the spiritual education once provided by the Sufi orders and the need for reviving an effective language of spirituality. We were delighted to learn that he is also closely associated with our dear friend, Shaykh Fadhlalla Haeri, and thus deeply acquainted with the path of spiritual experience. He has also held positions of responsibility as Minister of Trade and Minister of Defense in the cabinet appointed by the Interim Iraq Governing Council from September 2003 until 2004, and subsequently Minister of Finance in the Iraqi Transitional Government between 2005 and 2006.

The following is an excerpt from Ali Allawi’s The Crisis of Islamic Civilization (With permission from Yale University Press).

The recovery of the sacred, which is integral to any hope for the recovery of Islamic civilization, revolves around the notion of ihsan, the third essential dimension of Islam. In the sensibility of the times, this might veer towards tedious or sanctimonious moralizing, but ihsan has nothing to do with controlling or moulding outer forms of behaviour. It is a conscious pursuit on the part of the individual to perfect virtuous qualities which are associated with the inner spiritual journey. This pursuit was undertaken in the past through affiliation to the various Sufi tariqas, which had millions of adherents and adepts, or, in the Shia lands, through the more individualist and even solitary path of irfan, the metaphysical form of Sufism, which was acceptable to the Shia consciousness. The tariqas cannot be compared to the monastic orders of Christianity, if only because of their scale and ubiquity in Islamic public life. The modernist and Islamist assault on the spiritual paths of Islam destroyed a crucial form of organization which had encouraged the inculcation of moral qualities in the mass of the population as well as in the elites. It was not replaced with anything better than just an alternative: of either a dry ‘rationalist’ or scholastic Islam, or the doubts and moral ambiguities which are a feature of secular life. The ihsan aspect of Islam was degraded over time and, with it, nearly all the features of Islamic life that were marked by charitable works, communal solidarity and social concern. . . Although the traditional Sufi orders may be well past their prime as a vehicle for spiritualizing the masses, the deeper yearning which they had earlier addressed still remains.

Recovering the Transcendent in Islamic Spirituality

Excerpted from Ali Allawi’s The Crisis of Islamic Civilization (Yale University Press)

The erosion of ethical consciousness in Muslims is due to the weakening of systems which nurtured and protected this consciousness. Apart from the bedrock of the Muslim family, which always acted as the upholder and transmitter of ethical traditions, the social organizations of Muslims at work and worship were also instrumental in providing the scaffolding for their ethical universe. These organizations were not entirely Sufi in form, but most had incorporated the significance of perfecting moral characteristics, though in a vague and unsystematic manner. The remnants of the natural courtesy, generosity and concern for others that are still evident in certain urban classes in the Muslim world are a faint echo of that widespread condition well into recent times. The disorientation resulting from an opposition between the requirements for success (or just survival) in the modern world and the need to maintain an inner moral balance demanded by the religion of Islam has not been successfully mediated. The outer rules of the Sharia – whether modernized or not – or the acceptance of modern norms and values by a rationalizing Islam do not provide the moral compass which can keep Muslims on an even keel. The imbalance frequently leads to despair and violence, or to a lingering sense of personal betrayal of one’s traditions and values. Nihilism, reactionary thinking and rigid conservatism are born out of this anxious state of being

The conservatives, modernists and rationalists in Islam have always looked askance at the spiritual quest of individual Muslims. When seen through the prism of the rationalists, mysticism is a false system of thought based on superstition, hallucinations, mythologizing and unsubstantiated states and experiences which border on the insane. Modernists see in the aspects of folk Islam the worse kind of primitiveness, mass indoctrination and reasons for a severe embarrassment to their claims of Islam’s compatibility with the modern world. Political Islamists follow in the queue of their virulent anti-Sufi predecessors and see in the traditional orders vestiges of antique systems which often follow hereditary leaders and stand in the way of their own totalizing ideologies. Conservatives are fearful of the claim to an inner authority, which supersedes the Sharia and may lead to lax religious practices and dissoluteness. The role of the guiding sheikh in the life of the Sufi orders also creates a parallel religious authority structure to the traditional ulema classes.

There was no doubt that the Sufi orders, with a few exceptions, atrophied and sank far below their ideal, and there was an element of truth in all these critiques. Together they have seriously undermined the legitimacy and pertinence of the traditional Sufi orders – though not of Sufism as a reflector of the inner dimensions of Islam. Although the traditional Sufi orders may be well past their prime as a vehicle for spiritualizing the masses, the deeper yearning which they had earlier addressed still remains. In fact it may well have increased, as ex-Islamists join lapsed Muslims fleeing to avoid the ravages of modern hyper-competitive life and look for a home in the spiritual universe. The loss of an outer spiritual reality has not yet fully erased its inner consciousness.

However, the present age cannot easily admit to the validity of this type of knowledge and requires a confirmation that goes beyond the assertion of its traditional tenets. This applies to human beings generally and to modern Muslims in particular. The collapse of totalitarian systems has been equated with the victory of reason over irrationalism – what the social philosopher Karl Popper called ‘the most important intellectual, and perhaps even moral, issue of our time’: whether reason takes precedence over emotions and passions as the mainsprings of human action. The type of knowledge embodied in intuition, inspiration and guidance is firmly of the nonrational kind, one that cannot be subject to the empirical tests of scientific inquiry or to the rationalizing logic of the intellect. In consequence, it has been relegated to the outer circles of mystical pseudo-knowledge and denied legitimacy as a tool for understanding the world and humans’ place in it. The prejudice runs deep and crosses cultures and civilizations.

Knowledge of the unseen in Islam is not a revolt against reason in the same manner, for example, as racist or nationalist philosophies. It never claims to have the total truth but only one aspect of it, whose mastery is necessary in order to complete the human potential to understand the divine. The mysticism which the rationalists scoff at aims to establish the validity of this form of knowledge. It is placed in the same category as, for example, Platonic idealism, and is dismissed as an escapist fantasy with no bearing on humanity’s condition or travails. Islamic spirituality is not an exclusivist matter, in spite of the claims of some savants and mystics that it is indeed a superior form of knowledge. No true master of the path would make such a claim. It is a knowledge for which certain people have a profound taste, but their commitment to it does not necessarily lead to their denial of other forms of knowledge.

The western bias against irrational thinking, into which mystical knowledge is lumped, is based on the latter’s emotive and passionate content. Once again, Islamic inner spirituality has little to do with emotion and passion, but a lot to do with the systematic striving for an understanding of the attributes of God and the imperative of moral conduct that such seeking generates. The outer forms of the ecstatic states of the Sufis may reflect an inner ‘drunkenness’, a spiritual intoxication, but this is not the path towards knowledge of God. It may lead to the experience of the unseen, but this is a uniquely individual act, of little or no social consequence. True spiritual knowledge presupposes that individual self realization is only a transit station to social action.

The three fields of knowledge in Islam – the knowledge of the inner way, the knowledge of outer realities and the knowledge that connects the two – meld into each other but maintain their distinctness. None can claim an exclusivity or priority over the other, and none by itself is capable of rendering or understanding the truth. The subtlety of this relationship is embedded in Islam, and, according to Islam, in all the great religious traditions of mankind. All three balls have to be kept up in the air all the time. The comprehending, balanced and ethical human being realizes this in his or her knowledge, conduct and actions. The system of argumentation which is critical of rational thinking may be valid for, or within, one aspect of the tripod of knowledge, but it dissolves the connecting thread between the three fields if it is given absolute precedence. This phenomenon is akin to the process of observation in quantum mechanical systems. The very act of observation or measurement changes the initial conditions of the system and renders the results incomplete or indeterminate. Isolating one of the tripods for critical investigation may yield results for that particular field of knowledge but not for the whole, unless knowledge of the whole infuses the process. Keeping one’s eye on one ball while being aware of the relative position of all three balls to each other keeps the system afloat.

The unifying tendencies of Islam are not the same as the grand totalizing schemes of philosophers or political theorists. Islam is not an ‘idea’ that can be put alongside others, such as the Platonic Ideals or the Hegelian Spirit or the Nation. Neither is it a rationalist perspective on man and society which might be compared and contrasted to other empirical or rationalist theories. Society has a reality in Islam, for example, and is not a set of interpersonal relationships based solely on the fact of individuals dealing with each other. The absurd statement of Margaret Thatcher, Britain’s prime minister in the 1980s, that’ … there is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women, and there are families’, has no echo in Islam because, while partially true – all groups are composed of individuals ~ it destroys that truth by conflating an aspect of it with the whole. Similarly, a collective or idealist definition of truth is necessarily incomplete, and can be often tyrannical. It destroys the possibility of an individual’s autonomy for freedom of action.

Islam’s would-be reformers have fallen into the very same trap when they focus on an aspect of Islam and claim that its overhaul, re-reading or reinterpretation will create the conditions for the elevation of Muslims. That does not invalidate the critical examination of Islam’s legacies but it limits its interpretative potential. Once this limited methodology for assessing Islam’s legacy becomes the norm, it will hold no brief for its better understanding or practice. Islam will cease to be the reality for Muslims and become yet another system of belief or reasoning. A knowledge, or at least an awareness, of the comprehensive nature of Islamic knowledge should be a precondition for the investigation of the nature of Islam. Al-Ghazzali understood this and tried to reflect it in his synthesis. Of course, the scope and scale of knowledge is vastly greater now than it was in the medieval Islamic period, but this does not vitiate the need to be aware of the present state of knowledge. In fact it makes it even more vital.

However, the starting point for reinventing Islamic civilization must be the independent existence of a uniquely Islamic interpretation of the world, with an ethics rooted in the religion of Islam at the base of the rebirth of Islamic civilization. The nature of knowledge becomes not just a scholarly or philosophical subject but one that goes to the heart of the matter. A literalist faith almost automatically denies the validity of knowledge which emanates from traditions that do not acknowledge the same foundations. Islamic culture then becomes almost parasitic, unable to contribute to the betterment of humankind, yet a consumer of the products and services of others while it smugly asserts its ‘superiority’.

This is not far from the vision – and reality – of the Salafist literalists and their jihadi fringe. A ‘liberal’ Islam, on the other hand, is a curious amalgam of western norms and values with their ever-changing composition and a private spirituality which follows, selectively, esoteric aspects of Islam. This kind of Islam is in reality a part of the western tradition – a religion that is not much different from the ‘westernization’ of other world faiths (for instance, Buddhism in the West). It is unfortunate that such an Islam is frequently conflated with Sufism, which, in the West at least, has become an almost separate religion or cult, as its Sharia aspects are allowed to atrophy.

The Recovery of the Transcendent

Traditional Islam spoke of the three dimensions of the religion: Islam, Iman, Ihsan, that is, ‘good works’, ‘faith’ and the ‘perfection of qualities’. They are based on the Hadith of the Prophet’s encounter with Gabriel, from which also emerged the classic formulation of the ‘five pillars’ Islam: prayer, fasting, zakat, hajj, and enjoining the good and prohibiting evil. Essentially, these pillars gave the Muslim’s world an outer, institutional and legal, framework; a doctrinal and theological basis for religious belief; and, finally, an inner spiritual journey where the virtues were elevated and direct experience of the transcendent was sought. The dimensions of Islam are in reality little different from those of other religious traditions, especially the Abrahamic faiths. The world view practices of a Christian monastic would not differ, in substance, from those of his or her Muslim counterpart. But in Islam these elements of religion must be aspects of a single whole and not compartmentalized and separated as secular modernity would demand.

The effects of the tumultuous changes which have engulfed the Muslim world in recent times may not have sundered the interconnectedness of these aspects of Islam, but they have certainly muddled and weakened them. Most Muslims would fiercely affirm their faith – an open assertion of atheism or even agnosticism in the Muslim world is still extremely rare. At the same time, the majority of Muslims — at least those that have been exposed to a secular education and a modern lifestyle – do not make an easy connection between the sacred and the world around them. The Islamists are no better in this regard than the arch-modernists. Both are embarrassed by, or overlook, the significance of the unseen in Muslim consciousness and in the construction of Islam’s world view. In fact the entire Quranic revelation is addressed to ‘those who believe in the Unseen’.3 If one does not believe in the unseen, it is difficult to see how one can claim to reconstruct an Islamic civilization.

Most people automatically equate the sense of the transcendent with the type of overtly religious societies which have been rejected in the West. This experience, whether in Europe or America, has not been a generally happy one. The examples of an overbearing priesthood, a prim and hypocritical public piety, rigid conformity in personal and social behaviour, conjure up all that is antithetical to the free human spirit. Very few people in the West have any hankering for the Puritan world of seventeenth-century Massachusetts, the priggish bourgeois life of mid-Victorian England, or the stifling official religiosity of Franco’s Spain. But the experience of the transcendent in Islamic society, at least up to the modern period, is in no way comparable to that of the West since the Renaissance. Islamic society was not structured along officially religious lines in the conventional sense of the word. The closest approximations to such a society in the western experience were probably the traditional societies of medieval Europe, where the sacred was fused into the ordinary lives of people.

Modernity did not affect Islam just by separating state from religion, but also by reducing the natural sense of the sacred in people’s daily lives. The secular elites in the Muslim world behave no differently from their western counterparts in their ambivalence or hostility to increasing the role of religion in society. Even the terms of disdain and opprobrium used to describe such a possibility draw from the western experience. ‘Fundamentalism’, ‘a return to the Dark Ages’, and other such terms and phrases, are liberally used to describe the increased religiosity of Muslim society, even when they have no referents in the Islamic tradition. Nevertheless, these categories have stuck and basically define the debate, as Muslims have become increasingly distant from experiencing the transcendent in their world.

The recovery of the sacred, which is integral to any hope for the recovery of Islamic civilization, revolves around the notion of ihsan, the third essential dimension of Islam. In the sensibility of the times, this might veer towards tedious or sanctimonious moralizing, but ihsan has nothing to do with controlling or moulding outer forms of behaviour. It is a conscious pursuit on the part of the individual to perfect virtuous qualities which are associated with the inner spiritual journey. This pursuit was undertaken in the past through affiliation to the various Sufi tariqas, which had millions of adherents and adepts, or, in the Shia lands, through the more individualist and even solitary path of irfan, the metaphysical form of Sufism, which was acceptable to the Shia consciousness. The tariqas cannot be compared to the monastic orders of Christianity, if only because of their scale and ubiquity in Islamic public life. The modernist and Islamist assault on the spiritual paths of Islam destroyed a crucial form of organization which had encouraged the inculcation of moral qualities in the mass of the population as well as in the elites. It was not replaced with anything better than just an alternative: of either a dry ‘rationalist’ or scholastic Islam, or the doubts and moral ambiguities which are a feature of secular life. The ihsan aspect of Islam was degraded over time and, with it, nearly all the features of Islamic life that were marked by charitable works, communal solidarity and social concern.